ON THE RIVER AT 801 SOPHIA STREET IN DOWNTOWN FREDERICKSBURG, VIRGINIA

.jpg?crc=255392228)

Photograph

Children on the streets of Fredericksburg, possibly before 1887

A history of the Fredericksburg congregation that became Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site)

This abbreviated history was updated during February 2015 by the History and Archives Committee of Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site), consisting of Janice P. Davies, Bernice Easley, Faye Jones, Roland Moore, Mark W. Olson, and Dee Simmons, and it was updated and corrected slightly in November 2015

Web content copyright © 2015 by Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site), 801 Sophia Street, Fredericksburg, Virginia 22401

Note: Numbers in brackets, such as [1], refer to numbered source notes that can be found at the bottom of this page.

«« »»

Also note: Officially, this page is still somewhat "under construction." As of late November 2014, additional source notes and some photographs were still being added.

Sorrows and struggles, 1804–1854

It is believed that the first Baptist meeting house in Fredericksburg, Virginia, was established about 1804. The wooden building stood near what is now the Fredericksburg train station on Lafayette Boulevard. The congregation included white folks, enslaved and exploited black folks, and a few individuals known locally as “free Negroes,” though their freedom was in no way equal to that of the whites.

Blacks who sought membership were examined first by certain black brethren, then by a group of white deacons. Both groups had to be satisfied. Nearly all early churches in Fredericksburg had separate entrances for blacks (often a side door), as well as separate seating areas (often a crudely furnished gallery), for blacks.

The original wooden building remained the main gathering place for Fredericksburg’s Baptists until 1815. At that time, some members withdrew and began worshiping in a building along the Rappahannock River at what is now the present location of Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site)  Riverfront homes in Fredericksburg, 1863 at the northeast corner of the intersection of Hanover and Sophia Streets. This building, originally owned by the Bank of Virginia, was badly damaged during the great Fredericksburg Fire of 1807, which destroyed about half of the buildings in town. The damaged shell remained largely unused for a decade

Riverfront homes in Fredericksburg, 1863 at the northeast corner of the intersection of Hanover and Sophia Streets. This building, originally owned by the Bank of Virginia, was badly damaged during the great Fredericksburg Fire of 1807, which destroyed about half of the buildings in town. The damaged shell remained largely unused for a decade

By 1818, the Baptists expressed interest in constructing a larger, more permanent building on the site that contained the ruins of the earlier church. In April 1820, Horace Marshall and his wife, Elizabeth, sold the lot at what is now 801 Sophia Street to the trustees of “the New Baptist Meeting House” for $900. It is believed that a brick church building was erected on the site in the late 1830s or early 1840s. This building was known as “the Shiloh Baptist Meeting House.

Even before the building was constructed, the congregation was thriving. According to one published report, by September 1831, the congregation had approximately 300 “members of color.” According to other reports, by the late 1830s or early 1840s, the congregation had more than eight hundred members, three-quarters of whom were “people of color.” Although these members constituted a majority of the membership, it is possible that most of those present at Sunday services were white, as the “colored” membership came from a wide area encompassing the City of Fredericksburg, Stafford, Spotsylvania, and Caroline counties. Enslaved individuals were not always allowed (or able) to attend services on a regular basis.

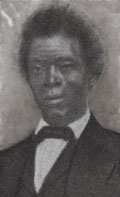

The original church building at what is now 801 Sophia Street had a balcony that wrapped around three sides of the sanctuary. On the Sundays when owners allowed their slaves to attend services, they entered the building through a separate side door that led directly to the gallery. Enslaved blacks sat in the side galleries, where they could  Noah Davis, ordained at Shiloh in the 1840s presumably be better seen by their owners sitting on the main floor. “Free” blacks sat in the end gallery.

Noah Davis, ordained at Shiloh in the 1840s presumably be better seen by their owners sitting on the main floor. “Free” blacks sat in the end gallery.

Sometime before 1844, Noah Davis, one of Shiloh’s enslaved members, was appointed as a deacon, but he longed to do more. He wanted to preach. This desire was in part due to his acquaintance with the Reverend Alexander Daniel, whom Davis considered “a bright and shining light among our people” and “the best preacher of color I ever heard.”  Although it is now a residence, during the 1850s, this building at Charles and Frederick streets served as the private jail for Fredericksburg's principal slave trader at that time, a man named George Aler

Although it is now a residence, during the 1850s, this building at Charles and Frederick streets served as the private jail for Fredericksburg's principal slave trader at that time, a man named George Aler

Davis shared his desire with the Reverend Armistead Walker, the enslaved leader of the African American portion of the early Shiloh congregation. Walker made Davis’s desires known to the “colored” members of the church, who supported his quest.

However, African Americans in Fredericksburg were not allowed to license any of their own for religious ministry. Because of this, Walker then took Davis’s request to “the white brethren,” who gave Davis a full hearing and granted him a license to preach.

Davis later wrote and published a memoir entitled A Narrative of the Life of Reverend Noah Davis, a Colored Man, Written by Himself at the Age of Fifty-Four that recounted his experiences in Fredericksburg and elsewhere. He had already purchased the  Prior to the Civil War, this auction block (which still stands in silent witness at the corner of Charles and William streets) was well known by early members of Shiloh for it was used for the buying and selling of human beings freedom of his wife and some of his children. Proceeds from the sale of his book helped him raise the money to purchase the freedom of his two enslaved children. In 2012, in recognition of Noah Davis’s achievements, the Library of Virginia recognized him as one of the “African American Trailblazers” in Virginia history.

Prior to the Civil War, this auction block (which still stands in silent witness at the corner of Charles and William streets) was well known by early members of Shiloh for it was used for the buying and selling of human beings freedom of his wife and some of his children. Proceeds from the sale of his book helped him raise the money to purchase the freedom of his two enslaved children. In 2012, in recognition of Noah Davis’s achievements, the Library of Virginia recognized him as one of the “African American Trailblazers” in Virginia history.

By 1849, some of those meeting for worship at the Shiloh Baptist Meeting House expressed interest in constructing a new and larger Baptist church building in Fredericksburg. This building, to be located at the corner of Princess Anne and Amelia streets, would be exclusively for whites.

A committee was established to seek financial pledges to underwrite the cost of construction. The committee recommended that the existing building at what is now 801 Sophia Street be “given” to the black membership upon completion of the new building for whites, provided that the “colonials” — the term used in the church minutes for slave owners — made a pledge of $1,100 or more toward the cost of the new whites-only sanctuary. After the “colonials” fulfilled this pledge, the black members would be “given” the building in which they had long worshiped.

Dreams and hopes, 1854–1862

Beginning in 1854 while construction was underway — and in anticipation of the forthcoming division of the congregation — black members of Shiloh began meeting separately on Sunday afternoons in the old building on the banks of the Rappahannock. This was the "holy ground" on which they had long worshiped. This was the "holy ground" on which they had sensed the liberating love of a God who confronts the Pharaohs of the world with a power that can shake loose all who are oppressed. For this reason, the largely African American congregation at 801 Sophia Street in Fredericksburg has long used 1854 as its starting date.

The break between the white and black segments of Shiloh’s congregation became official in 1855. When the new building on Princess Anne and Amelia streets  The new whites-only Baptist church on Princess Anne Street in Fredericksburg as it looked in 1864 opened its doors in the spring of 1855, the approximately 250 white members of what had once been known as “Shiloh” officially “dismissed” from their membership all 625 or more of their “colored brethren” (male and female).

The new whites-only Baptist church on Princess Anne Street in Fredericksburg as it looked in 1864 opened its doors in the spring of 1855, the approximately 250 white members of what had once been known as “Shiloh” officially “dismissed” from their membership all 625 or more of their “colored brethren” (male and female).

There was, however, some lingering financial tension. On March 26, 1856, the official board of the white congregation said it would support the establishment of a separate constitution for the “colored portion of the church” if the “colored” congregation would pay $500 “toward liquidation of the debt incurred in erecting the new church.”

How much of this was paid, and when, is not clear. In the minutes of the white congregation, the records show that they approved the transfer of the title of the 801 Sophia Street property to the “colored” congregation upon receipt of a note from that congregation stating they would pay $100 still due to the white congregation. It is known that a gift of $11.30 toward this cost was collected by the First African Church of Richmond and sent to Fredericksburg as a gift in support of their “sisters and brothers” on the Rappahannock.

The white congregation at the new location gradually began referring to itself as “Fredericksburg Baptist Church” rather than as “Shiloh” and informally referred to the church at 801 Sophia Street as “the African Baptist Church.” However, it seems as if most black Baptists in Fredericksburg continued to think of themselves as “Shiloh,” because this name had long been the church’s primary identity.

At this time, it was required by law that a white overseer be present whenever people of color held a church service. In 1857, George Rowe, a self-educated,  George Rowe, an ardent opponent of abolition, served as our legally required pastor/overseer for the last 5 years before the Civil War white Fredericksburg resident, became the congregation’s legally required pastor/overseer. He charged $50 a month for his services, to be paid by the free and enslaved members of the congregation.

George Rowe, an ardent opponent of abolition, served as our legally required pastor/overseer for the last 5 years before the Civil War white Fredericksburg resident, became the congregation’s legally required pastor/overseer. He charged $50 a month for his services, to be paid by the free and enslaved members of the congregation.

[For additional information on George Rowe, click here.]

In late November of 1857, the Reverend George Rowe baptized eighteen new members of his congregation in the undoubtedly chilly Rappahannock River. At that time, he reported to the local press that the congregation’s membership was in excess of 700 individuals.

Within five years, however, the outbreak of the Civil War had a monumental effect on the congregation. When Union troops arrived in the area in 1862, more than half of the congregation fled the degradation of slavery and racial discrimination that had prevailed in Fredericksburg. city to occupy free areas to the north. At some point in 1862, due to the destruction of the city caused by the Civil War and Rowe’s own failing health, regular Sunday services were discontinued. Rowe’s resignation as pastor/overseer took effect January 1, 1863, simultaneous with the formal declaration of Emancipation. He died three years later on January 18, 1866.

According to congregational records, during the period of time in which Rowe served as the official pastor/overseer, much of the actual preaching and spiritual direction was provided by the congregation’s own black deacons. In fact, one of those deacons, the Reverend Armistead Walker, is described in early documents as “one of the first ordained colored ministers” in Virginia. [26] According to a letter written on December 7, 1855, held in the archives of the James Monroe Museum and Memorial Library in Fredericksburg, Armistead Walker and George Rowe shared the pastoral duties at Shiloh.

Walker died on January 4, 1860. After his death, other African American deacons, including William J. Walker and George L. Dixon, continued to provide much of the preaching and spiritual leadership, while Rowe held the “official” position as pastor and overseer.

A fateful lightning, 1862–1865

Initially, the Civil War had little effect on Shiloh, though rumors and stories — as well as fears and hopes — must have abounded. In July 1861, the U.S. House of Representatives endorsed the army's emerging and previously informal "contraband policy." .jpg?crc=4089796196) President Abraham Lincoln with Union Army officers, 1862 This policy absolved "all army officers and soldiers from any moral, if not legal, obligation to return runaways."

President Abraham Lincoln with Union Army officers, 1862 This policy absolved "all army officers and soldiers from any moral, if not legal, obligation to return runaways."

The resolution approved by the House of Representatives had been introduced by Illinois Republican Owen Lovejoy. The resolution declared that "in the judgment of this House, it is no part of the duty of the soldiers of the United States to capture and return fugitive slaves" (quoted in Kenneth J. Winkle, Lincoln's Citadel: The Civil War in Washington, D. C. [New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2013], 236).

Consistent with this resolution, President Abraham Lincoln issued a formal opinion in August 18761, stating that in rebellious regions — which would include Fredericksburg — any slaves crossing to Union Lines were "thus liberated."

During the early years of the Civil War, slavery was still legal in the District of Columbia, but it was finally and effectively abolished in the District of Columbia by a bill signed by President Lincoln on April 16, 1862.

Two days later, on Good Friday 1862, Union troops moved into Falmouth, just across the Rappahannock from Fredericksburg. John M. Washington, an enslaved member of Shiloh Baptist Church in Fredericksburg, was working at the Shakespeare House Hotel on Caroline Street when news came of the advancing Union troops.  John Washington as he appeared in later years

John Washington as he appeared in later years

As the hotel’s customers and many white residents of Fredericksburg fled from the city, many taking their slaves with them, Washington boldly decided to test President Abraham Lincoln’s new contraband policy by escaping into Union lines. He persuaded a few others to join him. Consequently, he became the one of the first enslaved individuals to cross the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg during this phase of the war. Many others followed.

At least 400 of Shiloh's members fled from enslavement by making their way across the Rappahannock River while Union troops were encamped nearby, including many in August1862,

At least 400 of Shiloh's members fled from enslavement by making their way across the Rappahannock River while Union troops were encamped nearby, including many in August1862,

the month when this photo was taken According to early church records, about 400 of Shiloh’s members were among the thousands who fled to Washington, D.C., or other places.]

One early account notes that it was “only natural for these fellow church members to plan for a place where they might once more gather in prayer and praise God for their deliverance from the ravages of war” and the deep degradation of their past enslavement. As a result, twenty-one of the many individuals who had come from Shiloh in Fredericksburg began meeting together to organize a new congregation in Washington. Among them was Edward Brooke, one of whose descendants later became a United States senator from Massachusetts, and William J. Walker, a native of  William Walker, the nephew of our first pastor, Rev. Armistead Walker, was a preaching deacon at Shiloh in Fredericksburg prior to the Civil War, but during the war, he fled to Washington, D.C.., where he pastored two churches that were initially composed largely of refugees from Shiloh in Fredericksburg Fredericksburg and a nephew of the Reverend Armistead Walker.

William Walker, the nephew of our first pastor, Rev. Armistead Walker, was a preaching deacon at Shiloh in Fredericksburg prior to the Civil War, but during the war, he fled to Washington, D.C.., where he pastored two churches that were initially composed largely of refugees from Shiloh in Fredericksburg Fredericksburg and a nephew of the Reverend Armistead Walker.

Prior to the Civil War, William Walker had served with his uncle as one of the African American preaching deacons at Shiloh. While in Washington, D.C., Walker was ordained as a minister and became the founding pastor of what became known as Shiloh Baptist Church of Washington; according to an article in the Washington Post, by the time this church celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary in 1888, it had 850 members.

The Reverend William Walker also played an influential role in establishing several other Baptist churches in the District of Columbia, including Zion Baptist, Enon, and Mt. Jezereel. Even while serving as pastor of Shiloh Baptist Church of Washington, he preached at these other congregations.

Washington’s Zion Baptist was founded in 1864 by nine former members of Fredericksburg’s Shiloh who were living at the time in southwest D.C. They bought Simpson’s Feed Store and remodeled it as a building for church services and educational programs. The Reverend William J. Walker served as their first minister.

During much of the Civil War, back in Fredericksburg, services at Shiloh Baptist Church on the Rappahannock were largely nonexistent. Much of the membership had fled to Washington. Others had been taken out of the area by their enslavers. Given the large-scale destruction throughout the city and the frequent changes in the military situation, church life become anything but stable.

Shiloh’s building incurred significant damage during the Civil War. Like many buildings in Fredericksburg, the church was used as an army barracks. The sanctuary, located on the second floor, served as the hospital for the care and treatment of the wounded. The ground floor was used as a stable for military horses.

According to eyewitness accounts, the building suffered much destruction at the hand of troops that were under the command of Union generals Ambrose Burnside, Joseph Hooker, and Ulysses Grant. Windows and pews were removed or destroyed. All of the seats were pulled out of the gallery, as were the stairs leading to the balcony. The plaster ceiling was knocked apart, and certain support pillars at the back of the structure were knocked out, severely weakening one corner of the building. It would take the church years to recover from this wreckage.

At some point during the war, George Dixon, another of the refugees from Shiloh in Fredericksburg, was released from service as a guide to Union General Irvin McDowell. Afterward, he sought ordination from Nineteenth Street Baptist Church in Washington. Much like the Shiloh congregation in Fredericksburg, the congregation of Nineteenth Street Baptist had been “dismissed” from a previously racially diverse congregation that was becoming all white. This newly white congregation became known as First Baptist Church of Washington.

Down by the riverside, 1865–1878

At some point, either shortly before the war was over or soon after, the newly ordained Reverend George Dixon made a commitment to return to Fredericksburg to provide critical leadership for the church that he had left behind.  Fredericksburg's African Americans were often used to bury the diseased and partially decomposed bodies of fallen Civil War soldiers Some of Shiloh’s members had either chosen to remain in the area during the war or had been unable to leave. Others had joined the exodus to the District of Columbia but were now anxious to return.

Fredericksburg's African Americans were often used to bury the diseased and partially decomposed bodies of fallen Civil War soldiers Some of Shiloh’s members had either chosen to remain in the area during the war or had been unable to leave. Others had joined the exodus to the District of Columbia but were now anxious to return.

On December 24, 1866, Shiloh’s “Sabbath School” held its first post-war Christmas Eve program. It opened with a prayer by the Reverend Dixon, after which the assembled scholars sang “in a spirited manner” the Christmas hymn “Glory to God in the Highest.” The scholars, allowed to learn to read and write for the first time, read aloud in unison the second chapter of Matthew, after which they recited from memory the Ten Commandments and the Apostles Creed. This was followed by an “able address” by Dr. J. D. Harris, an African American physician who had come to Fredericksburg under the auspices of the Freedmen’s Bureau and who served as superintendent of Shiloh’s school.

By 1869, Shiloh was “growing rapidly in numbers.” In April 1871, Dixon was said to have baptized twenty-seven persons in the river on a single day.  Unfortunately, although we have George L. Dixon's signature on an old marriage certificate, we lack any photograph of him Anyone with a photograph or other information about Rev. Geroge L. Dixon is asked to contact the Shiloh Old Site archives committee by clicking here In March 1877, ninety new converts were baptized in a single afternoon. Most baptisms were conducted at “the old baptizing place” in the Rappahannock River, just above the railroad bridge. On one occasion, the local press reported that “more than a thousand spectators of both colors” came to the church for one of Shiloh’s baptismal efforts. In addition to aiding in the growth of the church’s membership, Dixon also obtained a $400 grant from the Freedmen’s Bureau to undertake some renovations of Shiloh’s badly damaged building.

Unfortunately, although we have George L. Dixon's signature on an old marriage certificate, we lack any photograph of him Anyone with a photograph or other information about Rev. Geroge L. Dixon is asked to contact the Shiloh Old Site archives committee by clicking here In March 1877, ninety new converts were baptized in a single afternoon. Most baptisms were conducted at “the old baptizing place” in the Rappahannock River, just above the railroad bridge. On one occasion, the local press reported that “more than a thousand spectators of both colors” came to the church for one of Shiloh’s baptismal efforts. In addition to aiding in the growth of the church’s membership, Dixon also obtained a $400 grant from the Freedmen’s Bureau to undertake some renovations of Shiloh’s badly damaged building.

Dixon was also leading the congregation’s African American members in political activity, including organizing Emancipation Day (New Year’s Day) marches through the streets of the city. According to a newspaper report, the march in 1870 included “several hundred colored persons” and concluded in the vicinity of Kenmore with speeches by Reverend Dixon and another colored man, Joseph Evars. A Shiloh-based benevolent society known as “the Good Samaritans” led the procession. In some other years, the procession ended at Shiloh, where the protection of the sanctuary was used for speeches. A brass band often provided music during the processions, and those that occurred after dark were torch-lit.

Dixon was active in the local Republican Party, sometimes serving on the committees that nominated candidates for the state legislature. In 1869, one of the individuals he helped nominate was a former Union Army officer, Captain Edwin McMahon. The candidate admitted to the local press that he would probably be seen by some people as a carpet bagger, and he said that within that “carpet bag” he carried his deepest sentiments, the sentiments on which he would stand or fall. In 1876, Dixon was one of seven African Americans who ran, unsuccessfully, for Fredericksburg’s City Council.

In 1878, Dixon resigned as pastor, confessing to the congregation that he had violated the seventh of the Ten Commandments. After approximately one year’s time, he was again accepted as a pastor, serving churches in Spotsylvania and Caroline counties while continuing to live in Fredericksburg. In time, his relationship with Shiloh was restored, and he served as guest speaker on special occasions. Although he died in 1907 in Philadelphia, where he had moved to live with a daughter, his body was returned to Fredericksburg and interred in the Shiloh Cemetery, located in the neighborhood that is now below Marye’s Heights and the University of Mary Washington.

.jpg?crc=406354594) Lemuel Walden, who served as pastor for three years beginning in 1878 Toil and trouble, 1878-1887

Lemuel Walden, who served as pastor for three years beginning in 1878 Toil and trouble, 1878-1887

In the autumn of 1878, the Reverend Lemuel Walden assumed the pastorate and later helped establish the Shiloh Cemetery. A Shaw University graduate, Walden served Shiloh for three years before accepting a pastorate in Boston, Massachusetts. Following Walden, the Reverend Willis Robinson arrived in 1881, and he faced the task of rebuilding the confidence of the congregation while also restoring a building weakened by flooding and the continued effect of damage during the war. In 1882, land on what is now Monument Avenue was purchased from A. P. Rowe for use as the Shiloh Cemetery.

Through rallies and other innovative projects, Robinson raised $1,500 for repairs to the building, but the deacons of the church voted to postpone action until the full amount needed could be raised; however, this delay proved ill-advised. Willis Robinson began pastoring here at Shiloh in 1881; after the division of the congregation, he became pastor of Shiloh Baptist (New Site), later also serving as pastor of Mt. Zion Baptist in Fredericksburg .jpg?crc=277188198) On June 11, 1886, following a meeting of the Grand Lodge of the Good Samaritans, a thunderous crash rocked the area as the rear wall of the building collapsed and left the structure unrepairable and requiring demolition.

On June 11, 1886, following a meeting of the Grand Lodge of the Good Samaritans, a thunderous crash rocked the area as the rear wall of the building collapsed and left the structure unrepairable and requiring demolition.

After the building’s collapse, the congregation met in the Fredericksburg Courthouse for nearly a year. During this time, deep divisions emerged within the congregation. At one point, Shiloh’s trustees purchased a lot at Princess Anne and Wolfe streets for $600. They planned to construct a new building for Shiloh on that site, which, at the time, contained a large brick building known as the Revere Shop. Some members wanted to move the congregation to that new location; others insisted on rebuilding on the original location. The congregation was almost evenly divided.

The last business meeting of the combined congregation was at the courthouse in May 1887. The Reverend Robinson was not present. Frank Phillips, a leading member of the congregation, presided. There was much division over what to do. By late May 1887, some of Shiloh’s members began meeting on Sundays at the Revere Shop, with the Reverend Robinson in charge. Other Shiloh members, opposed to use of the new site, continued meeting at the courthouse with preaching provided on an interim basis by a Reverend Jones.

Thriving and striving, 1887-1910

Legal questions concerning title for the new property arose in June 1887, resulting in an injunction prohibiting any new construction on the new site.

By late 1887, the Reverend James E. Brown, a native of Chesterfield, Virginia, assumed the pastorate of the congregation that remained at the courthouse, while Robinson continued as pastor of those who were meeting at the new site in the Revere Shop. Both groups considered themselves the “true” Shiloh Baptist Church and wanted to use the church’s name. On November 30, 1888, a local judge issued a final decree, ordering a compromise and division of assets, with each group using the name Shiloh Baptist Church with the addition of either “Old Site" or “New Site.” By May 1889, both groups had approved resolutions resolving all conflicts, and the division of assets was complete by July 1889. The congregation remaining at 801 Sophia Street would be known as Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site).

The Reverend James Brown oversaw the laying of a cornerstone for a new building on the old site on June 18, 1890. This festive ceremony included members of the Garfield Light Infantry and the Masonic Lodge #4 A. F. and A. M. The church was constructed by renowned local carpenter and builder C. G. Heflin of C. G. Heflin & Bro.  A festive outdoor service of worship andthanksgiving

A festive outdoor service of worship andthanksgiving

was held in June 1890 to mark the laying of a cornerstone for construction of our current sanctuary Charles Granville Heflin was born in 1867 as the oldest child to Carter and Alice Heflin. His younger brother, Elmer G. “Peck” Heflin, went on to become one of the most prolific and well-known architects in turn of the century Fredericksburg. Opening ceremonies were held on October 26, 1890.

Brown continued as pastor until 1905, during which time the church thrived. In 1891, just a year after the new building’s construction, the local press reported more than two hundred children in regular attendance at the Sunday school.

On August 28, 1905, the Reverend John Allen Brown, a Washingtonian, became the pastor. During his tenure, a central bell tower was added to the Sophia Street side of the new building. After five years of service, he left to go to St. John Baptist Church in Arlington, Virginia.

Hopes and visions, 1910-1961

The Reverend John C. Diamond became the pastor of Shiloh (Old Site) on November 18, 1910. Born July 22, 1877, he was a graduate of Hampton Institute and Howard University. During his time as pastor, the federal government paid for some of the damage caused by Union troops during the Civil War. In addition to serving as pastor, he was an architect and skilled builder. He used these skills to construct an addition on the back of the building. While construction was underway, human bones, identified as the remains of Union soldiers, were found on the river side of the building. In early July 1916, these were reinterred in the Fredericksburg National Cemetery.

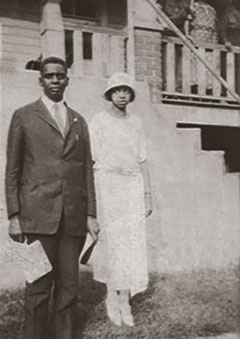

Pastor John Diamond and his wife Theresa visit members in their homes, about 1914 For a while, Reverend Diamond taught part-time at the Fredericksburg Normal & Industrial Institute (F.N.&I.I.). Also during his time as pastor, the church purchased some property on Amelia Street, where Reverend Diamond oversaw the building of a parsonage. The first stained-glass windows in the church were also installed under his leadership.

Pastor John Diamond and his wife Theresa visit members in their homes, about 1914 For a while, Reverend Diamond taught part-time at the Fredericksburg Normal & Industrial Institute (F.N.&I.I.). Also during his time as pastor, the church purchased some property on Amelia Street, where Reverend Diamond oversaw the building of a parsonage. The first stained-glass windows in the church were also installed under his leadership.

After the United States entered World War I, a group of local citizens organized to raise money for the United War Work Fund. This was a combined effort of the Young Men’s Christian Association, the Young Women’s Christian Association, the National Catholic War Council, the Jewish Welfare Board, the War Camp Community Service, the American Library Association, and the Salvation Army to promote “high standards of morality” among soldiers and sailors and to aid them in resisting “temptations” as they returned to civilian life. Reverend Diamond of Shiloh (Old Site) served as chairman of the city’s efforts. The local group collected $17,542.15, of which $1,226.25 came from the black community.

Reverend Diamond served Shiloh until 1920. He returned frequently thereafter as a guest speaker.

The next pastor, the Reverend B. H. Hester, was selected in 1921 and formally installed in 1922. He had received degrees from Biddle University in North Carolina in 1918 and from Virginia Union University in Richmond in 1921.

He was a gifted writer and educator and served for some years not only as the principal but also as a teacher and coach at the F.N.&I. fI. It served for many years as the only educational institution in the area open to African Americans who wished to pursue a high school education. Reverend Hester began as Fredericksburg Normal & Industrial Institute’s principal in the fall of 1929.

By 1918 Fredericksburg paid the school $1,000 a year for each “colored” school-age citizen of the city who enrolled. This provided less than was needed for much-needed improvements. In addition, the school admitted students from Stafford, Spotsylvania, and Caroline counties. Their modest tuition and board covered only a portion of the costs. Additional funds for the institute, informally known as Mayfield High School, were raised in part by individuals and groups at Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site). Although most of the groups and organizations contributing to the school were black, a few prominent white residents also made contributions. For example, in 1918, the school reported that artist Gari Melchers of Falmouth had contributed $10.

The school initially held classes in an old farmhouse that had once been known as Moorefield. To raise money for future construction, the school sold unneeded land acquired with the farmhouse. As they were developed, these new residential lots gradually became the neighborhood currently known as Mayfield. Thanks to the sale of lots and additional assistance provided by Shiloh (Old Site) and others, the Fredericksburg Normal & Industrial Institute was able to move into a new more academically oriented building on November 16, 1925.

The new building was used for its original purpose for only thirteen years. The city built a new elementary school for black children on a lot near Gunnery Spring in 1935. Three years later, the city expanded the facility and asked secondary school students from F.N.&I.I. to move to that building. This allowed a single principal to oversee both the elementary and secondary education of African Americans. In time, the combined institution acquired the name Walker-Grant in recognition of Joseph Walker and Jason Grant, both of whom had been instrumental in the founding of F.N.&I.I.  B. H. Hester, shown here in 1925, served as our pastor for 40 years, during which time he was a visionary and often outspoken and successful champion of racial, economic, and political justice in keeping with his passionate understanding of Christ and Christ's ways

B. H. Hester, shown here in 1925, served as our pastor for 40 years, during which time he was a visionary and often outspoken and successful champion of racial, economic, and political justice in keeping with his passionate understanding of Christ and Christ's ways

In 1923, Reverend Hester instituted a “Night School” at the church for adults who sought to increase their skills or overcome their illiteracy. This church-based educational effort continued for at least four years, with enrollment running as high as 300. Students ranged in age from sixteen to seventy-five. Said Reverend Hester about the school, which met every Monday, Thursday, and Friday evening during the school year, “You are never too old to attend.…Can you read the constitution? Do you wish to qualify to vote? If so, come out and join us. We have taught people to read and write in six months and can teach you to do the same.” The cost for those “who are able to pay” was $1 per month, but those without funds were welcome to attend without charge.

In January 1925, Reverend Hester initiated a newsletter called The Shiloh Herald. Although it was published by Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site), it provided a wide range of local news to the black community: who was ill, who was recovering, who had died, who had married, who had been born, who had had out-of-town visitors, who had recently traveled north, and so forth.

The Shiloh Herald was also instrumental in providing a strong African American perspective on important justice issues, a voice that was otherwise not available in the local media. Its motto, published in every issue, was “For all things beneficial and uplifting; against all things injurious and detrimental; neutral on nothing.” Reverend Hester, who served as editor-in-chief, explained at one point that he believed a responsible press should work “to change conditions in America and make them what they should be.” Courage was required, he said, because a truthful and responsible press needed to “stand before demagogues and damn their treacherous flatterers without winking.”

Editorials in The Shiloh Herald regularly sought to embody this understanding. For example, a March 1927 issue addressed the action of the U.S. Supreme Court in invalidating a Texas law that had prohibited black Texans from voting in that state’s Democratic primary elections. In Texas at the time, these were the only elections that really mattered because African Americans, who had typically been the primary group in Texas voting Republican, had been effectively disenfranchised during general elections, thus assuring a final victory for whoever won the Democratic primary.

Every week in the late 1920s, the Shiloh Herald delivered local news of interest to African Americans, news that was often not published in the local press; it also delivered strong, outspoken editorials on voting rights, lynchings, white arrogance, Supreme Court decisions, and more  Editorials in The Shiloh Herald pulled no punches, as can be seen in these excerpts from an editorial addressing the Supreme Court’s decision in the case known as Nixon v. Herndon:

Editorials in The Shiloh Herald pulled no punches, as can be seen in these excerpts from an editorial addressing the Supreme Court’s decision in the case known as Nixon v. Herndon:

Any ignoramus could have easily seen that such a law was unconstitutional and any court in hades would have declared it so at first sight. The fact that such a law found its way to the Supreme Court shows that something is radically wrong in America…. The Negro has been satisfied too long with decisions in his favor, when the courts making them were not concerned with backing them up…. What the Negro needs is not more decisions, but sentiment in his favor. He needs a government that will treat all its citizens exactly and precisely alike.

Another 1927 editorial pointed with shame toward what it called the tiny “den” at the city’s railway station that is “called a waiting room for colored people.” And why is it, the same editorial asked, that “whenever a crime or wicked deed has been committed in a community the Negroes are suspected and their homes are searched?”

In like manner, a strongly worded 1926 editorial, presumably by Reverend Hester, described those “who seek to keep others in ignorance and weakness” as “dangerous demagogues,” cutting at the very life of the nation. “The strength of a nation does not depend,” he wrote, “upon its standing armies or latent resources but upon the peace, prosperity, and satisfaction” of its “weakest citizens.”

Four months later, The Shiloh Herald strongly criticized a prominent white pastor from Richmond who had been “trying to pick a fuss with the Queen of Rumania [sic]…because a few Baptists in far-off Rumania are not allowed to worship as they please.” Such a concern was utterly misplaced, argued The Shiloh Herald, for the individual in question had expressed no concern whatsoever about the ongoing horror of U.S. lynch mobs:

We suggest to Dr. McDaniel that he can start a timely fight without going to Rumania. He can go to the office of Governor Byrd and inquire concerning the Wytheville lynching, why the investigation stopped so abruptly; or he can go to the state of South Carolina and insult the governor there because of the recent lynching of three human beings, one a woman; or he can go to the state of Texas and inform the governor that it is not right to allow a mob to burn three people at one time, especially not when one is a woman; or he can go to the White House and start a fuss with the great silent man, Calvin Coolidge, by telling him to use his great influence to have the Dyer Anti-Lynch Law passed.

Four members of the Shiloh Herald staff shortly after the paper got going in 1925A team of “distributors” delivered the four-page weekly paper directly to African American homes in Fredericksburg. Distribution of The Shiloh Herald continued for at least three years, probably more.

Four members of the Shiloh Herald staff shortly after the paper got going in 1925A team of “distributors” delivered the four-page weekly paper directly to African American homes in Fredericksburg. Distribution of The Shiloh Herald continued for at least three years, probably more.

During the first half of the twentieth century, many prominent African Americans spoke at Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site). Among them were Thomas Calhoun Walker, a Richmond lawyer who promoted education and land ownership among African Americans and served as a legal protector of many endangered African American youth; the Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Sr., founder of Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church; W. E. B. Du Bois, an outspoken African American sociologist, historian, and educator; Mary McLeod Bethune, widely known as an educator and civil rights activist; and Nannie Burroughs, an African American educator, feminist, religious leader, and civil rights activist.

In 1923, under Reverend Hester’s leadership, money was collected for purchase of a Moller pipe organ for the church. Many individuals and groups in the congregation (especially Julia Sprow Ross Frazier) worked hard to raise money through bake sales, musical programs, and other efforts. The installation and dedication of the organ was celebrated during a series of music-filled weeknight services, May 18–22, 1925. During this time, although relationships were still strained with the city’s white Baptists, Shiloh (Old Site) enjoyed mutually supportive relationships with the city’s Presbyterian and Episcopal congregations. For example, the pastors of both the Presbyterian Church of Fredericksburg and Trinity Episcopal Church attended one or more of the weeknight organ dedication services, offering public words of greeting and support.

In July 1925, with funds still needed to complete payment on the organ, a helping hand was extended by the Reverend R. V. Lancaster, pastor of the Presbyterian Church of Fredericksburg, who invited Shiloh’s choir, joined by other local African Americans, to provide an outdoor, Sunday evening concert of spirituals on the steps of the Presbyterian Church. A crowd gathered, and at the conclusion of the singing, which was reported to have left the audience in tears, the Reverend Dudley Boogher, pastor of St. George’s Episcopal Church, provided a sermon, after which a free-will offering was collected, yielding $70.93 to be used toward the cost of Shiloh (Old Site)’s pipe organ, which remains in use to this day. Earlier that year, Reverend Lancaster of the Presbyterian Church had also been the featured speaker at the closing exercises for students enrolled in the night school at Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site).

In March 1925, the Reverend Hester single-handedly brought about a major change in the text and headline style of a major Richmond, Virginia, newspaper, the News Leader. Writing on church letterhead in his official capacity as pastor, the Reverend Hester addressed the editor of the News Leader, objecting to that newspaper’s repeated use of “derogatory” and “un-Christian” language in describing people of color. He particularly objected to the use of such terms as “darkie” and “coon,” which the paper had commonly used until that point. After some consideration of the Reverend Hester’s position, the editor of the newspaper wrote him at Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site), agreeing with his reasoning and announcing that from that time forward, those terms would no longer appear in the pages of the News Leader.

In 1927, the Reverend Hester researched, wrote, and published a history of Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site). On June 11, 1946, he received an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree from Virginia Union University.  During the 1941–1942 academic year, the faculty of Walker-Grant, the city's black high school posed for a photo, several members of Shiloh Old Site among themHe served the congregation and community until 1961, an illustrious forty years.

During the 1941–1942 academic year, the faculty of Walker-Grant, the city's black high school posed for a photo, several members of Shiloh Old Site among themHe served the congregation and community until 1961, an illustrious forty years.

On the evening of Thursday, October 15, 1942, after several days of heavy rains, the Rappahannock River began to rise. On the following afternoon, it reached a record stage of 45 feet above normal. The entire lower floors of Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) were inundated. Water rose to within 20 inches of the ceiling of the ground floor. Chairs, a piano, some small organs, hymn books, Bibles, and as many records and files as possible were moved to upper floors. Walls, woodwork, and floors on the lower level of the church were severely damaged. Some records were lost. No services were held at the church the following Sunday.

During the second quarter of the twentieth century, the building’s front side underwent an extensive renovation with the addition of a new façade. (Records of the exact date were apparently lost in the aforementioned flood.)

Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) repeatedly used portions of its scarce assets to meet the needs of the larger community. For example, in January 1949, the church contributed $3,744 to the building fund of Mary Washington, the city’s only hospital, which still maintained a strict racial segregation of its patients. Members of the church hoped that the hospital’s practices would change once a new building was constructed.

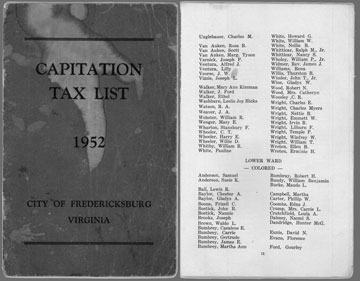

As late as 1960, "poll taxes" were regularly used in Fredericksburg in an effort to suppress the number of African Americans who would be able to vote; despite the burden this tax created, our pastor, the Rev. B. H. Hester, urged members of Shiloh Old Site to register and vote anyway Throughout Reverend Hester’s tenure as pastor, Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) played a strong role in working to see that as many local African Americans as possible were qualified to vote in local, state, and national elections. Through its night classes for adults, the church promoted greater literacy in an effort to overcome certain unjust obstacles to voting that had been imposed by the state. Despite the financial hardships involved, the church also actively promoted the paying of the capitation (“poll”) tax that was necessary to participate in elections in Virginia.

As late as 1960, "poll taxes" were regularly used in Fredericksburg in an effort to suppress the number of African Americans who would be able to vote; despite the burden this tax created, our pastor, the Rev. B. H. Hester, urged members of Shiloh Old Site to register and vote anyway Throughout Reverend Hester’s tenure as pastor, Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) played a strong role in working to see that as many local African Americans as possible were qualified to vote in local, state, and national elections. Through its night classes for adults, the church promoted greater literacy in an effort to overcome certain unjust obstacles to voting that had been imposed by the state. Despite the financial hardships involved, the church also actively promoted the paying of the capitation (“poll”) tax that was necessary to participate in elections in Virginia.

One of the key church and community leaders who emerged during Reverend Hester’s pastorate was Dr. Philip Y. Wyatt, Sr., a Charlottesville native, who opened a dental practice in Fredericksburg in 1933. Dr. Wyatt became Shiloh (Old Site)’s clerk, a presiding deacon, one of the church’s primary financial officers, a church school teacher, and when Reverend Hester’s health began to decline, he also often served as the church’s Sunday morning preacher.  Philip Wyatt, a leading member of Shiloh Old Site, was a key strategist in civil rights progress in Fredericksburg An outspoken advocate for racial justice, Dr. Wyatt during the 1940s became secretary of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). By 1953, he had been elected as president of the Fredericksburg chapter of the NAACP, a post he held through 1974. In 1953, he served as program chairman for the NAACP’s state conference, and by 1957, he had been elected as the organization’s Virginia president. He was reelected the following year, and remained in that position until 1960. He later served as co-chairman of the Fredericksburg Biracial Commission and as a member of the Virginia State Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Philip Wyatt, a leading member of Shiloh Old Site, was a key strategist in civil rights progress in Fredericksburg An outspoken advocate for racial justice, Dr. Wyatt during the 1940s became secretary of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). By 1953, he had been elected as president of the Fredericksburg chapter of the NAACP, a post he held through 1974. In 1953, he served as program chairman for the NAACP’s state conference, and by 1957, he had been elected as the organization’s Virginia president. He was reelected the following year, and remained in that position until 1960. He later served as co-chairman of the Fredericksburg Biracial Commission and as a member of the Virginia State Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Using his involvement in the church, the NAACP, and numerous other civic organizations, Dr. Wyatt was instrumental in pricking the conscience of the community so that the problems of minority inequities, inclusion, and opportunity were aired and addressed. While many cities in the nation were experiencing violence, destruction, and disruption, Fredericksburg remained relatively calm. It was Dr. Wyatt’s leadership, combined with skillful mediation and negotiations, that helped to maintain harmony and peace while historic changes were made.

As an officer of both Shiloh (Old Site) and the local NAACP, Dr. Wyatt frequently served as an informal advisor to members of the local African American community during various struggles in search of racial justice. One of the earliest of these encounters occurred in 1950. The only high school open at that time to African American students in Fredericksburg and southern Stafford County was the weakly funded Walker-Grant High School, located just off of Dixon Street in the city. In June 1950, the high school was preparing for its largest graduating class to date (27 individuals). It became clear that the school’s own facilities would be too small to host all of the students, friends, family members, teachers, and administrators who wanted to attend. On the advice of Dr. Wyatt, James Walker, the senior class president and a member of Shiloh (Old Site), approached the city. Mrs. R. C. Ellison, president of the Walker-Grant Parent Teachers Association and a member of Shiloh (Old Site), accompanied him. They asked for permission to hold the school’s commencement ceremonies at the city’s spacious Community Center, customarily used only by whites.

Initially, the city refused the request. Dr. Wyatt then advised James Walker on strategies in appealing the decision. Eventually, the city relented, agreeing that the black high school could use the Community Center for its commencement but stipulating that no student, teacher, or family member could enter through the front doors. All people of color would be required to enter and exit through a small side door near the back of the building.

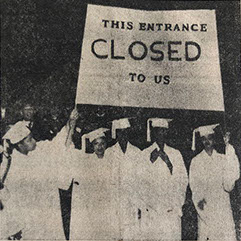

James Walker, the class president, reported this restriction to his class members and said that he would rather get his diploma on the sidewalk than be forced to enter the Community Center through the back door. Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) then stepped in and offered its facilities for the commencement. With Dr. Wyatt and Mrs. Ellison from Shiloh (Old Site) assisting with the planning and with the full backing of the Fredericksburg chapter of the NAACP, the Walker-Grant High School senior class then developed a plan to meet in caps and gowns on commencement day outside the front doors of the Community Center, holding large signs saying, “These doors closed to us.”

Members of Shiloh Old Site played key roles in planning and implementing a 1950 march protesting a decision by the city that denied black high school graduates and their families the right to enter the city's publicly funded community center through the front door A crowd of at least three hundred gathered in support of the demonstration. After the graduating class sang “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often described as “the Negro national anthem,” and heard a prayer, Dr. Wyatt presented two “dummy diplomas,” making a speech about how the class was “learning at the outset that life is filled with problems.” They then marched peacefully from there to Shiloh (Old Site), where the actual commencement ceremony was held. Although Shiloh (Old Site)’s sanctuary was smaller than ideal, it was a church that had supported and encouraged the class in its protest, and a number of Walker-Grant’s students and teachers were members of the congregation.

Members of Shiloh Old Site played key roles in planning and implementing a 1950 march protesting a decision by the city that denied black high school graduates and their families the right to enter the city's publicly funded community center through the front door A crowd of at least three hundred gathered in support of the demonstration. After the graduating class sang “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often described as “the Negro national anthem,” and heard a prayer, Dr. Wyatt presented two “dummy diplomas,” making a speech about how the class was “learning at the outset that life is filled with problems.” They then marched peacefully from there to Shiloh (Old Site), where the actual commencement ceremony was held. Although Shiloh (Old Site)’s sanctuary was smaller than ideal, it was a church that had supported and encouraged the class in its protest, and a number of Walker-Grant’s students and teachers were members of the congregation.

The intensity of feeling that the protest generated can be seen in a letter to the editor, published in The Free Lance-Star, by the Fredericksburg city attorney, C. O’Conor Goolrick. In his letter, attorney Goolrick called the protest a “childish demonstration” and suggested that “if the city is to be subjected to any more of these trumped-up racial protests, then, in my opinion, the best thing to do is to dispose of [the Community Center] by sale or lease to private owners.”

The next month, Fredericksburg’s NAACP responded to the situation by requesting use of the Community Center for a mass meeting to discuss educational inequalities in the city, voting rights, and an end to discrimination in transportation and other public facilities. A letter urging all local African Americans to attend the meeting was distributed at the city’s black churches, including Shiloh (Old Site), on the last Sunday of July 1950. Three of the letter’s four signers were members of Shiloh (Old Site): Dr. Wyatt, Willa Mae Coleman, and Jerry Taylor. Shortly after the letter went out, the NAACP’s request to use the facility was denied, allegedly because the building “had been spoken for” by a white “Youth Canteen,” though an African American citizen whose home was across the street from the Community Center entered the building at the requested hour of the NAACP’s meeting and found the auditorium in darkness, with only three men “laughing and talking” in one of the side rooms. The denial of access served to strengthen the commitment of Dr. Wyatt and other leaders at Shiloh (Old Site) to work for faster change on local, state, and national levels.

The congregation at Shiloh (Old Site) tried to support efforts in other locations as well. For example, on Sunday, March 18, 1956, the congregation collected a special offering in support of the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. The Fredericksburg chapter of the Virginia Voters League, in which Dr. Wyatt was heavily involved, regularly held its monthly meetings at Shiloh (Old Site). And in July 1961, the church hosted a mass meeting featuring the leader of protests against racial discrimination in Lynchburg, Virginia.

On behalf of Dr. Wyatt from Shiloh (Old Site) and twelve other named individuals, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., sent a letter on December 3, 1958, to a large number of black ministers in Virginia, urging them to rally their members to attend a nonviolent “Pilgrimage for Public Schools” to be held in Richmond on Emancipation Day (January 1), 1959. As a result of the letter, about eighteen hundred protesters marched two miles from the Richmond Mosque to the state capital.

In April 1960, Dr. Wyatt called a mass meeting in Fredericksburg, attended by about 350 of the area’s African Americans, to build support for “courageous members of our race who strive for true democracy in sit-in movements” to integrate some of the city’s whites-only lunch counters. At the meeting, Dr. Wyatt sharply criticized the Virginia General Assembly for “hurriedly passing anti-trespassing laws” and urged “100 percent support” by local African Americans for the new efforts.

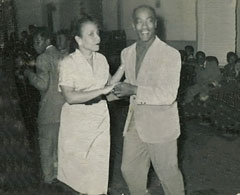

Gladys & Clarence Todd at the "canteen" that they founded for African American youth, who had been denied access to the city's white "youth canteen" Dr. Wyatt, Mamie Scott, and Gladys Poles Todd, all members of Shiloh (Old Site), trained about twenty local high school students for the sit-in effort, which began July 1, 1960, and continued throughout that month. Three downtown businesses were targeted: Woolworth’s, W. T. Grant’s, and Peoples Drug Store. Many of the participating high school students walked downtown from more distant neighborhoods, including Mayfield. Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) served as the staging and planning area for each day’s activity. Groups of students sat in at each location, rotating to a new location after an hour, while others picketed on the sidewalk in front of the business. Those sitting-in at the counter would occupy every third seat, which theoretically left seats available for other customers, but any other customer would thus have to sit next to an African American, which they knew most would choose not to do. However, as soon as the students would arrive, staff at each of the lunch counters would put out signs saying, “This Section Closed,” and as soon as the students left, the signs would be removed. After a month of protests, Woolworth’s and W. T. Grant (not joined by Peoples) announced a change of policy. To test the change in policy, seven African Americans, led by Dr. Wyatt from Shiloh (Old Site), immediately went to the two stores on the afternoon of July 30—and were served.

Gladys & Clarence Todd at the "canteen" that they founded for African American youth, who had been denied access to the city's white "youth canteen" Dr. Wyatt, Mamie Scott, and Gladys Poles Todd, all members of Shiloh (Old Site), trained about twenty local high school students for the sit-in effort, which began July 1, 1960, and continued throughout that month. Three downtown businesses were targeted: Woolworth’s, W. T. Grant’s, and Peoples Drug Store. Many of the participating high school students walked downtown from more distant neighborhoods, including Mayfield. Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) served as the staging and planning area for each day’s activity. Groups of students sat in at each location, rotating to a new location after an hour, while others picketed on the sidewalk in front of the business. Those sitting-in at the counter would occupy every third seat, which theoretically left seats available for other customers, but any other customer would thus have to sit next to an African American, which they knew most would choose not to do. However, as soon as the students would arrive, staff at each of the lunch counters would put out signs saying, “This Section Closed,” and as soon as the students left, the signs would be removed. After a month of protests, Woolworth’s and W. T. Grant (not joined by Peoples) announced a change of policy. To test the change in policy, seven African Americans, led by Dr. Wyatt from Shiloh (Old Site), immediately went to the two stores on the afternoon of July 30—and were served.

That same summer, two young members of Shiloh (Old Site)—Kenneth Wyatt and Gaye Todd—called on the local manager of Pitts Theaters to seek the privilege of sitting in any seat rather than those less desirable seats that had previously been designated for African Americans. The manager informed them that as of that moment, there would no longer be special seats for either whites or blacks.

After Reverend Hester’s death in 1972, his family remained active in the church. His granddaughter, Pamela Bridgewater-Awkard, served for many years in the U.S. State Department, including stints as U.S. ambassador or other official emissary in many nations, including Belgium, South Africa, the Bahamas, Benin, Ghana, and Jamaica.

Commitment and courage, 1962-2012

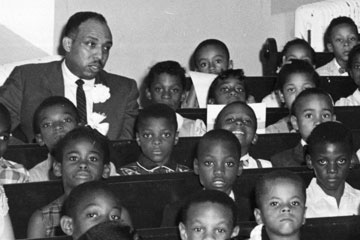

The Reverend Lawrence A. Davies, a native of Houston, Texas, with degrees from Howard University School of Divinity and Wesley Theological The Rev. Lawrence A. Davies with children at Shiloh Old Site during the summer of 1962 Seminary, became the pastor at Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) on March 4, 1962, and retired as pastor exactly fifty years later on March 4, 2012.

Seminary, became the pastor at Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) on March 4, 1962, and retired as pastor exactly fifty years later on March 4, 2012.

Six months after Reverend Davies began as Shiloh (Old Site)’s pastor, Roland Moore, a fourteen-year-old member of the congregation, became the first African American to be admitted to the city’s James Monroe High School. One of his aunts had been in the group from Walker-Grant High School that had been denied admission to the Community Center for that school’s commencement ceremonies. Although Moore’s enrollment at James Monroe had no coverage whatsoever in the local newspaper, it was widely known by some white parents and students. As a result, on his first day at the school in September 1962, he was greeted with a message scrawled in big black letters on the sidewalk: “Nigger go home.” During those early days when Moore felt utterly alone at the school and treated unjustly, he often sought and received advice and encouragement from Dr. Wyatt, Shiloh (Old Site)’s long-time spiritual and civil rights leader.

Although Fredericksburg’s schools were still functionally segregated and unequal, the city, in response to a federal court order, had quietly adopted a “free transfer” policy that technically allowed students the opportunity to attend the school of their choice, though the process of doing so was anything but easy. As a result, three other black students joined Moore at James Monroe for the spring semester. Two of them—Von Nelson and Clarence Robinson—were also members of Shiloh (Old Site). Dorothy Nelson, Von Nelson’s mother and a long-time member of the church, had herself participated in the 1960 sit-ins to integrate Fredericksburg lunch counters. She knew the kind of insults and difficulties her son might face, but she wanted him to be among those breaking the color barrier at James Monroe High School. The hostility that he faced was so intense that Von Nelson begged repeatedly to be allowed to go back to the all-black Walker-Grant High School. His mother refused. Integration was the future, she insisted.

In June 1963, fifteen months after Reverend Davies’ arrival and less than a year after Roland Moore became the first student of color at James Monroe High School, Fredericksburg’s City Council elected Clarence R. Todd, a member of Shiloh (Old Site), as the first African American member of the city’s school board. (Gilbert Coleman, another member of Shiloh [Old Site], was named to the school board in July 1971.)

Despite the addition of a single African American to the school board, not much progress was being made in desegregating the schools. Thus in May 1964, Dr. Wyatt sent a letter on behalf of the Fredericksburg NAACP to the school board, arguing that the board’s “free transfer” policy was not adequate. Dr. Wyatt called for a complete desegregation of students, faculty, custodians, and administrators “no later than the opening day of the 1964–1965 session.” He suggested that without compliance, litigation would be initiated.

After integrating its schools, the city of Fredericksburg initially refused to provide bus service to any of its schools, some of which were five miles from African American homes; in response, Janice Davies (pictured here with her three daughters) organized charter buses for school-age children, with a major portion of the cost provided by Shiloh Old Site Church; eventually the city was shamed into providing integrated bus service for children of all neighborhoods Although this continued pressure, much of it from people at Shiloh (Old Site), eventually led to the much-needed integration of the schools, with a single school for each group of grades, the city continued for a time to discriminate in the provision of certain services. For example, no bus service was offered, despite the fact that some school children—disproportionately black school children—now lived as much as five miles from the school that they were to attend. In response, the Home Missions Committee at Shiloh (Old Site), under the leadership of Janice Davies, chartered a bus to provide daily transportation for school-age residents of certain neighborhoods, and the newly formed Mayfield Civic Association chartered a similar bus to provide school transportation for students in that part of the city. Eventually the city was shamed into providing bus service for all students.

After integrating its schools, the city of Fredericksburg initially refused to provide bus service to any of its schools, some of which were five miles from African American homes; in response, Janice Davies (pictured here with her three daughters) organized charter buses for school-age children, with a major portion of the cost provided by Shiloh Old Site Church; eventually the city was shamed into providing integrated bus service for children of all neighborhoods Although this continued pressure, much of it from people at Shiloh (Old Site), eventually led to the much-needed integration of the schools, with a single school for each group of grades, the city continued for a time to discriminate in the provision of certain services. For example, no bus service was offered, despite the fact that some school children—disproportionately black school children—now lived as much as five miles from the school that they were to attend. In response, the Home Missions Committee at Shiloh (Old Site), under the leadership of Janice Davies, chartered a bus to provide daily transportation for school-age residents of certain neighborhoods, and the newly formed Mayfield Civic Association chartered a similar bus to provide school transportation for students in that part of the city. Eventually the city was shamed into providing bus service for all students.

Marguerite Young, a member of Shiloh (Old Site) who had been born on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, began teaching in the city’s segregated schools in 1957. After the schools were integrated, she moved to James Monroe High School where she became assistant principal. Recognizing her administrative skills, the school board then made her principal of Maury School. She was the first African American to serve as principal in the city’s newly integrated educational institutions. She eventually became director of instruction for the city's schools.

In 1963, Mamie Scott, a member of Shiloh (Old Site) who had been active in the NAACP and in planning for the 1960 lunch counter sit-ins, made some further waves in the city. She decided to try to integrate one of the city's white churches. She applied for membership in Fredericksburg's previously all-white Methodist church. When the newly installed pastor of that congregation decided to accept her application for membership, controversy developed. Mrs. Scott, however, wasn't one to give in easily. She persisted, even when a significant number of that church's members rebelled, splitting off to form what eventually became Fredericksburg's Grace Memorial Church.

Soon after his arrival, Reverend Davies and other members of Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) began working for a greater African American impact in local and state elections. Further impetus for the effort occurred in October 1963, when the Virginia Conference of the NAACP held its annual convention in Fredericksburg, with Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) serving as convention headquarters. Fredericksburg mayor C. M. Cowan was invited to address the gathering but refused. Some local African Americans felt snubbed by his refusal to make an appearance. Perhaps in response, that autumn’s voter registration drive, led by Dr. Wyatt, resulted in more than a 30 percent increase in the number of “colored citizens” who had paid the poll tax and would thus be eligible to vote in the next local and state elections. This was despite obstacles the city imposed on first-time registrants, who were required to pay both the current year’s poll tax as well as the tax for two prior years, plus a financial penalty for not having paid the prior year’s poll taxes when they were due.

In the midst of marches being led in Selma, Alabama, in March 1965 by the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., and just two days after President Lyndon Johnson spoke to a televised joint session of Congress to urge passage of the Voting Rights Act, a two-hour picketing demonstration by local white and Negro residents was held in front of the city courthouse. Dr. Wyatt of Shiloh (Old Site) explained to the local news media that the demonstration was in support of the marchers in Selma and the voting bill introduced by President Johnson, as well as a protest against Virginia’s continued use of a poll tax.

In the early 1960s, in an effort to build on the increased voting strength of African Americans in Fredericksburg, Reverend Davies and church deacon Weldon Bailey, a local mortician and resident of the city’s Mayfield neighborhood, organized a political action group known as Citizens United for Action. By 1965, through careful behind-the-scenes strategies and determined get-out-the-vote efforts, they were able to provide the needed margin of votes to influence the outcome of both a primary election to determine the Democratic candidate for the House of Delegates, as well as the outcome of the general House of Delegates election itself.

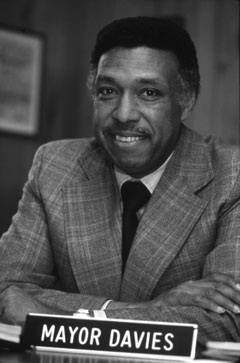

In 1966, while serving as pastor, Lawrence Davies became the first African American elected to the city council; in 1976, he was elected as mayor, serving five terms, more than any other Fredericksburg mayor before or since  Shiloh (Old Site)’s Weldon Bailey was also able to foster a more welcoming environment at one of the city’s polling places, having been appointed in 1965 as one of the city’s first African American election judges. These victories led to increased attention to African American perspectives in future campaigns and laid the groundwork for future victories.

Shiloh (Old Site)’s Weldon Bailey was also able to foster a more welcoming environment at one of the city’s polling places, having been appointed in 1965 as one of the city’s first African American election judges. These victories led to increased attention to African American perspectives in future campaigns and laid the groundwork for future victories.

One fruit of this early effort became evident in 1966 when Reverend Davies became the first African American elected to Fredericksburg’s City Council. He was elected as the city's first black mayor in 1976. (Perhaps significantly, the 1966 city election was the first in which payment of a poll tax was not required for voting.) He was reelected as mayor four times, retiring from that post in 1996 after having served for longer than anyone in the city's history. As mayor, he was the driving force in establishing a low-cost public transportation system that would serve those who lacked any other way of getting around. The city’s central bus station was subsequently named in his honor.

Early during his years at Shiloh (Old Site), Reverend Davies took an active interest in the mental health of the community, expressing a strong concern for those who were struggling with various kinds of limitations and disabilities. He served as a regional vice-president of the Virginia Association of Mental Health, served on the board of the Rappahannock Area Community Services Board, and in 1969 was awarded the Pratt Mental Health Citation for “the greatest service as a volunteer in the field of mental health in the past year.” In 1972, Reverend Davies founded the Fredericksburg Area Sickle Cell Association, which has continued to provide critical educational and support services for families dealing with sickle cell disease.

In 1968, at Reverend Davies’ urging, Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) partnered with the Human Relations Council in applying for federal loan guarantees that would allow construction of the city’s first subsidized-rent housing units to be known collectively as Hazel Hill Apartments. Federal approval of the project, intended to benefit the city’s low-income residents, many of whom were African American, was announced in early December  After Hurricane Agnes in 1972, the Rappahannock River rose up to Caroline Street in downtown Fredericksburg, doing great damage to the first floor of Shiloh Old Site's building 1969. It was only the second such effort in the state. Shiloh (Old Site) and the city’s Human Relations Council jointly created the Hazel Hill Apartment Corporation to build and manage the project. Reverend Davies and Dr. Wyatt served on the project’s board. Roland Gray, another member of Shiloh (Old Site), served as the corporation’s initial treasurer.

After Hurricane Agnes in 1972, the Rappahannock River rose up to Caroline Street in downtown Fredericksburg, doing great damage to the first floor of Shiloh Old Site's building 1969. It was only the second such effort in the state. Shiloh (Old Site) and the city’s Human Relations Council jointly created the Hazel Hill Apartment Corporation to build and manage the project. Reverend Davies and Dr. Wyatt served on the project’s board. Roland Gray, another member of Shiloh (Old Site), served as the corporation’s initial treasurer.

Hurricane Agnes brought major flooding to the Rappahannock River in 1972. Flood waters rose above the first-floor level of Shiloh’s building. Years of church records, some of which were stored in the basement, were damaged or lost. Under the leadership of the Reverend Davies, the whole first floor underwent extensive repair.

In 1976, the educational annex was constructed, adding classrooms and offices on two levels. An elevator and handicapped restrooms were added in the annex in April 1992. The church acquired some adjoining land, known as the Gillis property, in 1982. The house on that property was torn down in 2005.

In March 2003, the congregation had to vacate the 1890 sanctuary because the sanctuary roof was in need of major repairs. For four months, the congregation shared Sunday worship services with Friendship Baptist Church in Stafford but continued to use other parts of its Sophia Street building. The entire roof was rebuilt, and the ceiling of the sanctuary was elevated to provide better viewing angles from the balcony.

Pastor Lawrence Davies joined with other downtown pastors in forming Micah Ecumenical Ministries to minister in Christ's name on behalf of some of the most marginalized members of our community; in 2014 he became Shiloh Old Site's pastor emeritus Reverend Davies worked closely with pastors of other downtown Fredericksburg churches, undertaking joint, ecumenical efforts of various kinds, becoming the first black president of the Fredericksburg Ministerial Association. Perhaps more significantly, he became one of the founding pastors of Micah Ecumenical Ministries, an outreach effort in which Shiloh (Old Site) continues to play an important role. Micah Ecumenical Ministries serves the most troubled and dispossessed local residents, including the chronically homeless.

Pastor Lawrence Davies joined with other downtown pastors in forming Micah Ecumenical Ministries to minister in Christ's name on behalf of some of the most marginalized members of our community; in 2014 he became Shiloh Old Site's pastor emeritus Reverend Davies worked closely with pastors of other downtown Fredericksburg churches, undertaking joint, ecumenical efforts of various kinds, becoming the first black president of the Fredericksburg Ministerial Association. Perhaps more significantly, he became one of the founding pastors of Micah Ecumenical Ministries, an outreach effort in which Shiloh (Old Site) continues to play an important role. Micah Ecumenical Ministries serves the most troubled and dispossessed local residents, including the chronically homeless.